John W. Snyder

Half 2nd g-granduncle of Jerry Piechocki, husband of Dorotha Piechocki

Private Co. E 19th MI Infantry

Dates of Service: 11 Jan 1864 - 10 Jun 1865

John W. Snyder was born Sep. 3rd, 1838, in

New York state, the son of Henry Snyder and his

[unknown] first wife. By 1860, 21-year old John

was living with his father, stepmother, and

stepsister in Hickory Corners, Barry County,

Michigan, where his father had a farm. [His future wife, Nancy Rogers, 9 years old, was living with her farming family in the same little village.]

On Dec. 30th, 1863, 25-year old John W. and his 19-year old cousin, George W. Snyder, enlisted as Privates in Co. E, 19th Michigan Infantry, at Hickory Corners, for a term of 3 years. They mustered in Jan. 11th, 1864, and joined their regiment at McMinnville, Tennessee, Feb. 1st,1864.

The 19th Michigan had been in service long before the enlistment of John and George. Truth be told, it was a hard luck regiment, having been routed by Confederate forces in three previous engagements with a majority of the regiment scattered or captured on three different occasions while in Tennessee. The regiment was comprised of less than 300 men in June 1863. Those captured were exchanged but could no longer be involved in this theater of war and were eventually pieced out to regiments in the Eastern Theater. At this time the regiment was reorganized by adding 600 new recruits and began training to be soldiers, learning to fire their Springfield rifles, use their bayonets, and to perform close order drill.

On Oct. 25th, 1863, the Regiment became part of the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 20th Corps, and was ordered to McMinnville, Tennessee, where it was employed in the construction of fortifications. The Regiment garrisoned there until April 21st, 1864, where it built several forts, constructed a railroad bridge, put a saw mill in operation along with other construction purposes, and drilled and trained even more. April 30th, the Regiment having been ordered to join its division, arrived at Lookout Valley and officially became part of William Tecumseh Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee. The Regiment made a demonstration at the battle of Buzzard's Roost, but was not engaged; it still had the stigma of the old 19th and was considered a raw regiment.

The Army crossed through Snake Creek Gap and engaged in the battle of Resaca, Georgia, on May 15th. Here the 19th was needed and participated in a full division charge on a Confederate battery. Four regiments spearheaded by the 70th Indiana were led by Colonel Benjamin Harrison (the future President). The division marched down the slope and into a small valley between two ridges and marched into their first taste of hell, marching 300 yards toward the four artillery pieces and the dug-in Confederates. The last 100 yards were at the run, charging into the guns, which was now firing canister “that was so close as to blow the hats off our heads” wrote Private William Sharp. Reaching the guns and driving the rebels back, the division took up a defensive position and traded volleys until nightfall. Under the cover of darkness the captured guns were pulled out of their positions and became Federal property. All four regiments involved claimed credit for the capture. The 19th’s losses in this charge were 14 killed and 66 wounded. Now they were veterans.

As the Union Army of the Tennessee pushed the Reb army deeper into Georgia the 19th was called upon in many engagements. On May 19th, the Regiment made a charge at Cassville while protecting the Army's left flank, losing 1 killed, 4 wounded. Engaged again at New Hope Church on the 25th, the 19th was involved in an ill-fated attack through deep thickets along with a 20,000-strong force led by General Joseph Hooker. The force was trapped under cannon and rifle fire from the ridge above. It was not until night fall and a torrent of rain were they able to withdraw. The two divisions lost 1,665 men, with the 19th losing 5 killed, 47 wounded.

On the 10th of June they were engaged at Golgotha Church, which was a rear guard engagement by Patrick Claburne’s Battalion. Several regiments attempted to break through with the 19th losing 4 killed, 9 wounded in the attempt. Yet again the 19th was engaged at Culp's Farm, with another rear guard defense where they lost 13 wounded. Following up on the retreat of the Confederates from this position to Kenesaw Mountain, the 19th was held in reserve and fortunately did not participate in the disaster that occurred while trying to capture that mountain fortress. Instead, a large section of the Army moved around the Kenesaw, thus flanking it and forcing the Confederates to the breast works around Atlanta. The 19th along with the 3rd Division crossed the Chattahoochie River to participate in the repulse of the Confederates’ attempt to smash General Thomas’s forces at Peach Tree Creek on the 25th of July. The outcome was very much in doubt with the outnumbered and out-flanked Union lines begining to crack. The entire 3rd Division lunged into the Confederate position on the ridge that covered the fields. This so excited General Thomas who yelled “Hurrah! Look at the 3rd Division. They’re driving them!” After two hours of fighting the Confederates’ counter attack by Patrick Cleburne’s famous division, the Rebs knew they could not succeed and pulled back into the Atlanta earthworks. The Federal death toll of the day was about 1,700. The 19th lost 4 killed, 33 wounded, of which many would die of wounds later. During the Siege of Atlanta, the 19th Regiment suffered 2 killed, 6 wounded. The Regiment then advanced on Atlanta, only to find it evacuated, there to remain on garrison until October 30th, 1864.

On the 15th of November, the 19th Regiment, in the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 20th Corps advanced with General Sherman on the “March to the Sea,” or as the troops called it, “The Big Walk,” marching 2,000 miles from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia, marching through the burning hulk of Columbus, South Carolina, and up to Alexandria, Virginia. All the way they were “making the south howl” by destroying property, ripping up railroads, freeing slaves and “procuring” all the food they could eat, leaving the area destitute for years to come. There were dangers -- Confederate cavalry constantly attacking the flanks and rear of the spread out forces, and local infantry who captured Union soldiers foraging and hanged them. There was also a new threat: land torpedos (mines) that were place in roads causing terrible wounds. Yet the army reached Savannah on the 21st of December and spent Christmas there, resting and refitting with supplies brought in by the Navy.

Heading north in March 1865, the Regiment crossed the Cape Fear River, found and confronted the Confederates at Averysboro, North Carolina, on March 15th . This was an effort to hold up this arm of the army heading for Columbus. The 19th participated in yet another heroic charge, carrying the works, and capturing the artillery emplaced there, losing 4 killed, with 15 wounded. However, they were thrown back by a much larger force. On March 19th, the Confederate army executed a flanking attack on the forward elements of the right wing, near Bentonville, North Carolina. Although nearly defeated, the 3rd Corps was sent double-time to reinforce General O. O. Howard. No losses for the 19th were recorded. The Battle of Bentonville crushed all real resistance and allowed Sherman’s Army a clear path to Petersburg, where Robert E. Lee and his Army of Virginia was still held up.

With the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, all that remained was the surrender of General Joseph Johnston and the Army of North Carolina (for lack of a better name), which was accomplished on April 26, 1865.

With heavy hearts upon learning of the assassination of President Lincoln, but with the knowledge that the fighting was done, the Regiment was marched with the 3rd Corp, to Alexandria, Virginia, arriving there on the 18th of May while singing “Marching through Georgia” to participate in the Grand Review in Washington on the 24th. The Army had a little time to rest but never received replacement uniforms. While the Army of the Potomac paraded through dressed in their finest attire on the 24th, the Armies of the The Tennessee, the Cumberland and the Ohio marched through Washington D.C. on the 25th . They were unshaven and in their field uniforms, dirty, with dried blood on many of them and on hospital litters. The crowd was shocked at first but realized they were seeing what war was really about and what these fine troops had endured, and they applauded loud and long as the

Armies passed in formation.

The 19th then proceeded to Jackson, Michigan, where on the 13th of June it was paid off and disbanded. - Sources: 19th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment ; 19th Michigan Infantry in the Civil War ; 19th Regiment, Michigan Infantry ; Shelby Foote's "The Civil War: A Narrative" ; Time Life "The Civil War"

John W. Snyder was transferred to company A, Tenth Infantry, June 10th, 1865. He mustered out at Louisville, Kentucky, July 19th, 1865. John returned to his father's home in Hickory Corners and rejoined the family, which by this time included two little sisters. In 1872, he married Nancy M. Rogers, the daughter of Garrison and Loenia Wilder Rogers. John's father Henry died in 1878, and John moved about that time to Plainwell, Allegan County, where he worked as a laborer. By 1880 he and Nancy had two daughters, 6-year old Grace and 4-year old Bernice.

By 1884, John, Nancy and the girls had moved to Bay City, Bay County, Michigan, where John joined the Ralph W. Cummings Post #67 [later renamed the U.S. Grant Post], Bay City. John found work as a carpenter.

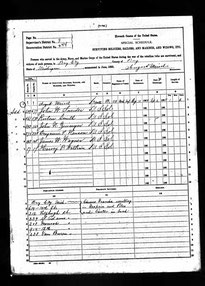

He was enumerated on the 1890 Veterans Schedule from Bay City as a veteran receiving benefits.

Nancy died Apr. 21st , 1901. John followed on Jul. 12th, 1906, at the age of 67. He and Nancy are buried in Elm Lawn Cemetery, Bay City, Bay County, Michigan.

Throughout their lives, the cousins had daring and emotional stories of their experiences spent during an extraordinary year and a half following and fighting for

“Uncle Billy” and, in their minds, winning the war of the rebellion.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES: Ancestry dot com; wikipedia; nps.gov; fold3; findagrave;

GAR Records Project

GRAVESITE: Elm Lawn Cemetery, Bay City, Bay County, Michigan

Written by Gerald and Dorotha Piechocki, April 2020

Updated May 2020